Theories of Change

We recognize the interdependence, whether intentional or unintentional, between all groups working to create healthy and sustainable changes in the Canadian food system and appreciate that each group functions according to its own theory of change. The transition coalition must therefore create and carry the capacity for groups to come together and collaborate within a movement ecology.

Personal Framework: Doing, Being, & Becoming

- Doing: The act of doing refers to personal occupation and performance of an individual. Engaging with others, taking part in activities of the individual, and producing and forming one’s own identity and shaping society are all required for social interaction.

- Being: This refers to being a genuine individual. The individual is responsible to think and reflect upon themselves. A person needs to understand his or her own role, the gift they have to give to the world, and maintain it.

- Becoming: As people embark on new roles, they redefine their priorities and rethink their values to prepare their transition. This is their becoming.

Three main theories of change

1) Personal transformation: Organizations and programs focused on changing lives one person at a time.

Ex. leadership development programs, spiritual counseling, 12-step recovery programs, diversity and anti-oppression training, food banks, job placement, and other social service programs.

The site of personal transformation is the individual. Personal transformation attends to people’s direct needs, and it projects a vision of change rippling slowly outward as individual lives are improved. This theory of change is based on the idea that when we are hurt and suffering, we are more likely to inflict hurt and suffering on the people around us. Conversely, when we heal these wounds and take a step toward personal liberation or wellness, we are more capable of healing and supporting those around us.

2) Alternative Institutions: Establishments and cultures that offer a new vision for the future are alternatives. They accomplish this by experimenting with new ways of doing and being.

Ex. worker and consumer cooperatives, credit unions, feminist bookstores, urban gardens, cultural spaces, and restorative justice programs

The goal of alternative institutions and cultures is to model new relationships and ways of interacting within our social, political, or economic worlds. Alternatives express the values we want to uphold, instead of values maintained by the status quo. Integral to this theory of change is the idea that successful experiments not only foster the wellbeing of those who participate in them, but can spur larger change. By proving the success of new and innovative arrangements, alternatives create prototypes that can be replicated and expanded on a broader scale.

3) Dominant Institutional Change: organizations working to alter or reform the dominant structures that shape society, such as corporations or government bodies.

Ex. labor unions, advocacy, mass protest movements, community organizing, and policy and litigation groups.

This theory of change focuses on reforming the laws, rules, or regulations within dominant institutions, so that the lives of people affected by those institutions are changed. The goal is to use organizing campaigns, public pressure, elections, or other methods to alter the behavior of these institutions.

- Inside Game: strategy of working withinexisting channels of bureaucracy to directly influence decision makers

The inside game includes any strategy working within insider channels to influence decision makers. Changemakers in this area leverage their proximity to powerful decision makers and use expert knowledge to lobby for reforms. Inside-game players may be vying for seats of power themselves, or they may be working closely with people already in power in order to influence decisions. Their focus is on using the established channels of change — such as elections, the legal system, and the current bureaucracy — rather than external pressure or changing the channels themselves.

Examples of the inside game include working with legislators to craft better policy, negotiating with corporate leadership, or using legal action.

Inside-game strategies play an important role, but they also have limits. Any political advocate can provide stories of times when insider channels get clogged and they are left with little influence or leverage. In these situations, lobby days, top-line research, and negotiating meetings are no longer enough to change an institution.

- Structure organizing is geared towards building organization. A structure-organizing group works to build an organized base of people to pressure decision makers around certain demands.

This base could be any constituency, including people living in a certain neighborhood or city, young people, people of faith, women, Latinos, or any other group. It could also be self-identified groups of people who care passionately about a given issue, such as animal rights or health care.

The most prominent examples of structure-organizing groups are labor unions and community-based organizations. Some leading figures in this tradition include Ella Baker, Saul Alinsky, and Walter Reuther.

Structure-organizing groups have a number of common traits and methodologies. They build power and resources through a long-term organization; they develop leadership through one-on-one relationships and committee building; and they believe that campaigns are won by exerting leverage on primary and secondary targets.

- Mass Protest: efforts build power by using a series of repeated, nonviolent, and escalating scenarios to create political crises that gradually generate a majority of active popular support for reform (e.g. passing an Act of Congress) or revolution (e.g. overthrowing a dictatorship).

Mass protest prioritizes action that is symbolic and expressive to build the movement’s profile with the public at large. A mass protest movement can consist of multiple organizations, sometimes working on multiple interrelated issues. Thus, such a movement needs to think about itself differently than a single Organization. Because mass protest acts as a catalyst, it can engage both inside players and structure groups. But, typically, mass protest will also produce new groups and new formations of people that sprout up outside of established institutions.

Examples of movements that included mass protest mobilizations include the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, the marriage equality movement, Occupy Wall Street, the Movement for Black Lives, and the Dreamer movement.

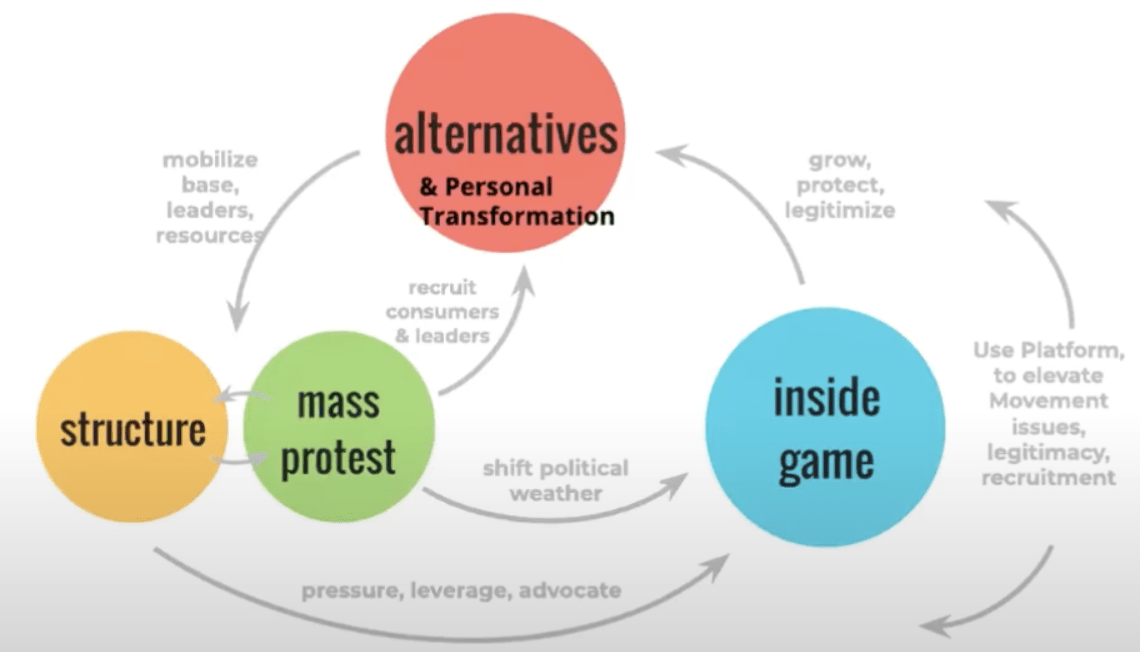

The below graphic helps us to understand the interrelationships between different theories of change. It demonstrates how we may work in a way that will generate and sustain a healthy change environment, facilitate success for each group and ultimately, enable us to collectively achieve meaningful, lasting, and just transformations in Canada’s food system.